Introduction

Child malnutrition is a significant issue in the modern world and is the leading cause of death among children in middle-income nations. Malnutrition refers to both undernutrition and overnutrition and is coined as the double burden of nutrition by the World Health Organization (WHO). Stunting, wasting, and being overweight are the indicators, presented by the WHO and UNICEF, which set the norm for assessing malnutrition for children globally. The population most at risk of being affected by malnutrition are women and children. Good nutrition is vital to promoting maternal, infant, and child health, improving educational performance, supporting stronger immune systems, and reducing the risk of diseases. Child malnutrition in the state of Gujarat, India will be analyzed to understand the health burden of malnutrition at a global and local level, and potentially identify effective intervention strategies. The intervention objective is to fully eradicate severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in children under the age of five in Gujarat, India.

Background

Malnutrition has various effects on children aged 1-5 years. According to the Joint Child Malnutrition report of 2018, created by the World Health Organization, UNICEF, and World Bank Group, 151 million children are stunted, 38 million are overweight, and 51 million face some form of wasting. Stunting is a developmental disorder where one’s height-to-weight ratio severely deviates from the average measurements observed globally. Wasting is physical degradation measured through the loss of muscle and fat tissue. Children experiencing wasting are more vulnerable to mental impairments due to lack of development at necessary stages and often develop oedemas formed due to swelling or fluid build-up as a symptom of starvation. Malnutrition increases the risk for diet-related noncommunicable diseases, it can affect individuals, households, and entire populations, and it can be chronic affecting people throughout their lifetime. For children specifically, malnutrition increases the chances of developing anemia, facing difficulties in education due to mental impairment, physical issues, susceptibility to noncommunicable diseases (specifically acute respiratory syndrome), and undernutrition in general which contributes to 45% of preventable deaths of young children annually.

According to a 2017 report by the Journal of Perioperative & Critical Intensive Care Nursing, “8.7 percent of children were stunted, 15.1 percent were wasted and 29.4 percent of children were underweight in India in 2013-14.” Anemia, which is an iron, Vitamin B, Vitamin A, iodine, and folic acid deficiency, affects 59% of children under five years of age in India. Iron is essential to the growth of children and women contributing to risk elevation for those two populations. Iodine deficiency disorders are the most common causes of mental impairments while Vitamin A deficiencies cause an estimated 0.5% of night blindness among children less than five years of age. Health interventions must consider all these consequences of SAM.

Gujarat has 41.6 percent of the overall stunted children in India, 18.7 percent of overall wasted children in India, and 33.6 percent of the overall underweight children. The Economist gathered data from the Rapid Survey on Children, UNICEF, and the Government of India to find Gujarat is home to 34 percent of children who are underweight. “Infants are very vulnerable to wasting, while stunting generally increases with age from early childhood to around 24 to 35 months (Harding et al., p. 10).

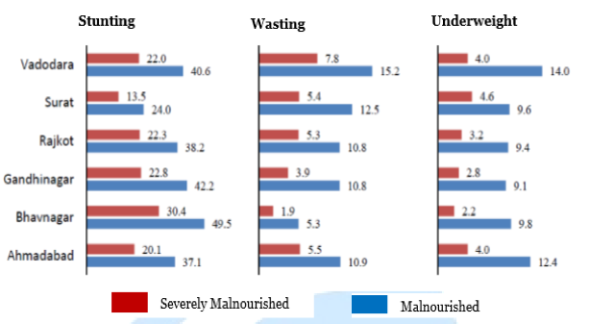

“The below graph shows the prevalence of malnutrition among children <5 yrs across the six administrative divisions in Gujarat, as per Comprehensive Nutrition Survey in Gujarat (CNSG), conducted under the aegis of the Women & Child Development, Govt. of Gujarat in 2014.”

Gujarat CSR Authority. (2015). Malnutrition Information Pack.Retrieved from GCSRA: http://gcsra.org/writereaddata/images/pdf/IP-Malnutrition.pdf, p 12.

Gujarat CSR Authority. (2015). Malnutrition Information Pack.Retrieved from GCSRA: http://gcsra.org/writereaddata/images/pdf/IP-Malnutrition.pdf, p 12.

In Gujarat, malnutrition affects more women than men and affects women for a longer period of time than men. From 1990 to 2016, malnutrition remained the number one risk to disability adjusted life-years (DALYs), affecting 14.6% of the child and maternal population while dietary risks, in general, came in second place affecting 10.4% of the population overall. According To the National Family Health Survey of 2015-2016 (an annual survey conducted by the Indian Government), malnutrition rates in children have generally decreased since 2006 but not by much. There are 38.5% of children under five in Gujarat who are stunted, 26.4% who are wasted, 9.5% who are severely wasted, and 39.3% are underweight according to the mean weight-for-age identifiers.

Consequences of Child Malnutrition

Malnutrition anthropometry, or measurement of body size and composition, has been set by the WHO and is the health burden measurement utilized globally. The major indicators include low-birth-weight in newborns, low-weight-for-age in preschool children, and low body mass index (BMI) for women. These indicators are further expanded upon using relative risk estimates for diseases and occurrences of diarrhea, malaria, measles, acute respiratory infections, and some other infectious diseases.

The first epidemiological study to identify a measurable relationship between malnutrition and child mortality rate conducted in the 1990s using eight community-based studies which all showed an inverse relationship between risk for mortality and weight-for-age. A monumental discovery of that report was that in all child deaths within developing countries, about one half has malnutrition as an associated cause. While severe malnutrition is extremely detrimental, most deaths are a result of mild-to-moderate malnourishment, the population that fell under the latter form of malnourishment was larger than the severely malnourished even in the 1990s and that trend has continued to present times.

The health burden of child malnutrition is severe in Gujarat; however, it is unwarranted. Gujarat, with a GDP per capita of $2,200, is one of the wealthier states in India with the resources, economic capability, and experience to eradicate child malnutrition. The inability of effective action taken can be further dissected by understanding the social determinants and risk factors that give rise to or influence malnutrition.

Risk Factors and Social Determinants Leading to Child Malnutrition

Direct social determinants for child malnutrition can be categorized into three major groups; economic status, education, and food systems. Access to land, clean water, education, certain markets, support systems, social protection, infrastructure, proper transportation, employment, income, technology access, information access, and marketing have all been shown to affect nutrition at a basic level. Another category for basic causes of child nutrition includes; culture and social norms, gender, fiscal and trade policy, legislation and regulation, agriculture, food systems, urbanization, climate change and pollution, and political stability and security.

A report by Harding, Aguayo, and Webb assessed wasting in South Asia with a focus on India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Through a quantitative analysis of multiple South Asian national surveys, wasting was correlated with various independent variables, and some conclusions were drawn about the social determinants and risk factors affecting child malnutrition. Specifically, “a multivariate mixed logistic regression and backward stepwise methods to identify parsimonious models for each country separately” was conducted (Harding et al., p.1).

A significant association between lower household wealth and the risk of child wasting was only found in India (Adjusted Odd Ratio for children in poorest households at 1.55). A correlation between the lack of an improved water source and region of residence was also strongly associated with wasting in India overall, specifically the states of Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, and Jharkhand. While most of the states on this list are fairly poor, Gujarat has the economic and agricultural capability to address child malnutrition head on.

Quantitative studies conducted by Bora and Saikia aim to identify neonatal and under-five mortality rates in various Indian districts. The authors identified two major reasons for the high rates of neonatal and under-five mortality associated with malnutrition present in India. First, there are prominent discrepancies in development across districts within India. For example, “census 2011 data shows that district-level female literacy rate varies between 24.25 to 88.62 percent; district-level urbanization varies between 0 to 100 percent and… safe drinking water ranges between 8.60 to 99.60 percent” (Harding et al., p. 9). Second, there is a disparity between the accessibility and availability of health infrastructure, human resources, and services in the health care system in rural areas specifically, despite past interventions to address this issue. The authors identified a clear geographical clustering of high-risk districts for under-five mortality with a particular clustering (124 districts) of under-five female mortality rates in the north, east, and west regions. Gujarat is in the westernmost part of India.

A study by Meshram, Rao, Reddy et al., is a comprehensive application of child malnutrition rates and application within the context of Gujarat. The authors conducted a community based cross-sectional study using a random sampling procedure to assess malnutrition in slums throughout rural and urban Gujarat. The sample size for this study was 2008 households from rural areas and 400 households from urban areas. Data for this study was collected keeping in mind all essential malnutrition measurement frameworks. Research assistants and field workers were trained in survey methodology; anthropometric measurements were gathered using a SECA weighing scale. History of morbidity during the 15 days preceding the survey was recorded, information about breastfeeding was synthesized, and maternal information;

“such as age, parity, antenatal care (ANC), tetanus toxoid (TT) immunization, receipt of iron & folic acid (IFA) tablets, and particulars of delivery, were collected from mothers of under 6 month children, a total of 3133 children (boys: 1594, girls: 1528; rural: 2600, urban: 533), with mean age of 26.2 ± 15.9 months, under 5 years were covered” (Meshram et al., p. 3).

The household wealth index revealed that overall wealth is significantly correlated with malnutrition. The socioeconomic status of the household overall is associated with lower purchasing power, lower literacy, and food insecurity. There is an important cultural factor that requires consideration in Gujarat. The state has various districts and each district is distinct. The Surat region, for example, has five districts all inhabited by different tribal populations. The Indian government created Anganwadi centers around rural India to monitor and implement strategies to address malnutrition and child hunger. The authors selected 20 of these centers from each of the five districts, the selected an additional 20 households with children under the age of five. There can be huge variations between natural groups of households, streets, mohallas or neighborhoods, and other distinctions of communities in India. To account for these differences, the authors grouped the selected Anganwadi centers into five geographical areas and noted, “households belonging to Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities formed one group” (Meshram et al., p. 3). This proved crucial for the findings because the authors discovered a correlation between tribal areas and malnutrition, which aligns with previous studies conducted by the NNMB in 2009, a study conducted by Meshram et al. in Maharashtra (a state neighboring Gujarat), and another study by the NIN in Madhya Pradesh in 2010 (a state which currently has the highest level of malnourished children) (p. 5).

A major risk factor for childhood malnutrition in India depends on the rural versus urban context, income level, education (especially of mothers), cultural contexts, and the geographical clustering of people in various areas (most often this has to do with cultural, tribal, and group histories). Interventions must consider the cultural, geographical, and income level discrepancies of children most affected by malnutrition in India by targeting certain districts and evaluating the available infrastructure within those areas.

Measurement

For any intervention to be successful there must be guidelines on accurate assessment of the presence of a health issue. In 2013, WHO developed assessment measurements and suggested potential interventions for severe acute malnutrition in children under the age of five via formalized guidelines to identify children with SAM using the mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) or a height-to-weight ratio (WHZ); “namely mid-upper arm circumference <120 mm, mid-upper arm circumference <130mm and weight-for-height <–2 Z-score” Additionally, the WHO identifies the presence of bilateral oedema (swelling due to water retention) as a measure of severe child malnutrition. These forms of measurement are easy to carry out as is often witnessed in the international community’s use of armbands to assess undernutrition and oedemas are physically distinct. The WHO has identified the risks of conducting randomized control trials to fully prove the accuracy of these forms of measurements, due to ethical concerns. Therefore, the best intervention and assessment strategy proposed by the WHO is based on past evidence of successful programs and projects carried out on the ground by the WHO themselves or other SAM related intervention projects.

While weight-for-height and mid-upper-arm circumference are the measurement tools most utilized for addressing child malnutrition the WHO has found that the agreement between using these two forms of measurement varies according to settings and geographic locations.

SAM has multiple short-term and long-term consequences for children. In terms of micronutrient deficiencies, it is identified that children with SAM often have Vitamin A, iron, and iodine deficiencies which can affect hormone levels for adequate growth and development of children, this can also influence mothers when they are pregnant with a child and be passed down to the child after birth. Nutrient deficiencies make children prone to communicable diseases, diarrhea, bacterial adherence (as mucus linings safeguarding against bacteria weaken) and generally weaken the immune system making a child susceptible to various illnesses. Therefore, simply addressing food intake is not sufficient, a child must be assessed for and treated as necessary for micronutrient deficiencies, water loss, oedema, communicable diseases, and long-term sustainability of health so chronic malnutrition does not occur, which is common for many low and middle-income nations where SAM interventions have taken place.

A ready to use therapeutic form of food (RUTF) was developed in the 1990s by the WHO which is fairly cost-effective, accessible, and an easy to transport treatment method. This is the standard intervention method utilized for addressing SAM in the short term. Additionally, the WHO has provided the framework for adapting inpatient versus outpatient visits of children with SAM in accordance to their clinical conditions, appetite, social circumstances, family concerns, mitigating circumstances, or significant social, cultural, or access issues. WHO guidelines outline how to measure oedema, micronutrient deficiencies, dehydration, HIV, and potential bacterial infections or illnesses a child may have. These multilateral consequences of malnutrition vary by location as some children may be hydrated but suffering from Cholera, some may be in shock due to water loss but not prone to bacterial infections, and some may be facing severe diarrhea and loss of appetite. Therefore, all these issues must be initially assessed in a new location to gain general information about the consequences of malnutrition present in an area before developmental projects are implemented. While the WHO provides an adequate overall framework for assessing and addressing SAM in children under five years of age, it often lacks in terms of evaluation and measurement of impact.

The World Bank created a report assessing all child malnutrition projects it sponsored to gauge effectiveness and cost efficiency of the projects it was funding. The projects were categorized into; conditional cash transfers, unconditional cash transfers, community-based nutrition, early child development, feeding or food transfers, integrated health services, deworming, micronutrient interventions only, and other (which generally included strategies such as nutrition education and gardening for nutritional resources). Covering 54 percent of low-income nations and 46 percent middle income nations, the World Bank has the most efficient guidelines on the best form of impact evaluations and measurement of intervention effectiveness pre-implementation, during the intervention, and post-intervention.

Literature Review

The Innovative Approaches for the Prevention of Childhood Malnutrition (PROMIS) study assess one of the most common forms of SAM interventions; a community-based management of child acute malnutrition (CMAM) via an intervention case study in Burkina Faso and Mali. PROMIS hopes to integrate prevention and treatment methods for addressing acute malnutrition for more sustainable impacts. PROMIS outlines a comprehensive map of survey-based (qualitative means) and data based randomized control trials (quantitative means) of gauging project effectiveness to better assess the cost-effectiveness or projects, successes of projects, and to absorb the background knowledge necessary for scaling up in the future.

In Burkina Faso and Mali children, ages 6-23.9 months are followed for 18 months. Measurement of the prevention strategy for the study includes small quantity lipid-based nutrient supplements (SQ-LNS) to combine behavior change communication (BCC) targeting food-insecure households with information on adequate health and diets for young children. With CMAM, children who have SAM but do not have strong complications (such as those secondary conditions outlined by the WHO like HIV or anemia), can be treated at home via Ready to Use-Therapeutic Foods (RUTF) with support from the primary health care facility. PROMIS was then used to evaluate the interventions.

While this intervention was successful in Mali and Burkina Faso, there have been many reports that discuss CMAM can often be a faulty intervention strategy due to community motivations, the effectiveness of BCC in specific community contexts, the need to address multiple issues not just SAM in relation to food, and many other variables. In terms of assessment of BCC, however, PROMIS is a good model as it evaluates projects using qualitative and quantitative measurements throughout an intervention project. While BCC is a usual form of preventive and sustainable change for SAM utilized by global health projects, it is not comprehensive in accounting for all the variables present in SAM affected areas. There must be a better understanding of the socioeconomic conditions and various other larger foundations present to efficiently address SAM multilaterally and sustainably.

Article 1

A study conducted in Mumbai India helped the Indian Government from 2013-2014 deliver Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) to 12,362 children in Mumbai slums through Anganwadi community health workers. The study revealed that Anganwadi health workers of ICDS can work efficiently with local health workers in slums throughout India to create more cost-effective health interventions.

“The community-based prevention and treatment programme averted 15,016 DALYs (95% Uncertainty Interval [UI]: 12,246–17,843) at an estimated cost of $23 per DALY averted (95%UI:19–28) and was thus highly cost-effective (p. 1). The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) is a welfare scheme launched in 1974 by the Government of India to tackle malnutrition and health problems in children below 6 years of age and their mothers. The programme offers health, nutrition, and hygiene education to mothers, supplementary feeding for children and pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, growth monitoring and promotion, and links to primary healthcare services. The ICDS is a welfare scheme launched in 1974 by the Government of India to tackle malnutrition and health problems in children below 6 years of age and their mothers.”

The ICDS used the Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) approach to treat SAM With four major components; outpatient RUTF distribution, a short-term inpatient clinic for stabilization, community mobilization, and a supplementary feeding program when appropriate. In the context of the Dharavi Mumbai slum area, the inpatient care and stabilization center had to be provided by a tertiary municipal hospital nearby instead of creating a special clinic for those services as is common with CMAM projects. This intervention also included WHO developed SPHERE minimum standards which are evidence-based standards for assessing the best practices for humanitarian response. SPHERE analysis revealed 44% of infants were not cured, 8% did not recover from SAM, 6% defaulted on treatment, and some were unable to receive full services.

The CMAM program has been known for its cost-effectiveness from previous interventions in Bangladesh, Malawi, and Zambia. India is no different, cost-effectiveness was measured at the cost per DALY averted at $24 per child. The cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) for this study concluded $335,126 for the yearlong intervention. The largest percentage of costs went to daycare expenditures at 14% and supervision and follow-up calculated at 12% each. An additional cost-effectiveness comparison across nations found the main cost item is usually administration (39%), followed by technical support (29%), management (13%), and day care centers (8%).

An important cost-effectiveness evaluation reveals India’s per capita GDP is $1570 (in 2013), therefore the estimated cost of $23 per DALY averted (and the $24 per DALY of this specific intervention) are both feasible and cost-effective nationally. The results of this study show a feasible model of intervention that can be implemented throughout India. Some recommendations for further improvements include altering the low cure rates by researching; “service delivery (e.g. the non-standard definition of discharge as cured, the use of WHZ versus MUAC, the lack of adherence to RUTF) or to household level factors (e.g. food insecurity).” Another recommendation includes removing the daycare component of the intervention in the future as not all afflicted children were able to utilize that program and due to its high burden of cost. However, the daycare center provided cognitive stimulation for the children which has been identified as a necessary component of child development and an intervention to long-term consequences of SAM. Overall, the Mumbai case study was an effective overview of the benefits to the government (ICDS) and community-led (Anganwadi/ SNEHA) collaboration for providing services to urban slums across India.

Article 2

A study in the Jharkhand state of India utilized the ICDS and Anganwadi Community health centers by evaluating interventions from 2016-2017 with a follow up in September 2017 to inform future policies. Screening two blocks within Jharkhand, 217 cases of SAM were identified out of 20,525 children. An outpatient clinic was set up in Chandankiyari (one of the blocks within Jharkhand) with training for staff including Auxiliary Nurse Midwives, 80 Accredited Social Health Activists or ASHA workers, and 160 Anganwadi workers. Training for staff was provided by the State Nutrition Mission and World Vision (WV) India. “WV India provided a dedicated CMAM coordinator for the pilot in addition to a network of 40 volunteers supporting nutritional screening, referral, and monitoring activities.” Children with further medical complications were referred to inpatient care at a local hospital. Conducting an eight-week long in-patient visit, children were provided with amoxicillin and immediate nutritional services via CMAM centers. If after eight-weeks children had a MUAC of >11.5 they were sent to the local hospital for further services. If the eight-week program was successful, however then the children were enrolled in Anganwadi or community centers for a supplementary feeding program like RUTF.

After implementation, 51 outpatient clinics were established, and 158 SAM cases were reported within a year. Halfway through the year, after a high referral rate to local hospitals (21%), a vaccination campaign was conducted through the Department of Health due to an outbreak of chicken pox and measles causing diarrhea or vomiting. Additionally, high default rates were observed due to multiple reasons: often the eight week program was seen as too long by parents; parents stopped bringing in children after the first few weeks yielded improvements thinking additional treatment was unnecessary; parents were concerned about poor tolerance to RUTF by some children (stools, vomiting); migration was common as people moved back to their rural villages when living in the urban slums became too difficult; parents were often too busy with work; or due to parents prioritizing attendance of local festivals over hospital visits.

There were political issues post-intervention which could be resolved through an agreement between State Nutrition Mission, Department of Health, and WV India. Another improvement suggested was to include a weight to height z score (WHZ <-3 SD or WAZ <-3 SD) as another qualification for admission as some children did not meet MUAC criteria but had symptoms of SAM or undernutrition. Overall, this study was one of the first to assess the efficiency of CMAM and results of a 61% cure rate and 39% defaulter rate point to the potential of the program and necessary reforms required for greater efficiency.

Article 3

Conducting a mixed-methods analysis of an NGO-government partnered intervention with a population of 300,000 people in informal settlements in Mumbai, this evaluation focused only on children under the age of three in Dharavi from 2014-2015. The Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA) provided services to pregnant women, children with SAM and those diagnosed with moderate acute malnourishment (MAM) using WHZ scores developed by WHO from 2011 to 2016.

The one-year program yielded $868,217 in costs with a majority going to project personnel (64%), while the rest was divided into administration and intervention at 33%, including costs for training, evaluation and monitoring, meeting and events, and other field expenses. Most of the costs were subsidized through the Nutritional Rehabilitation and Research Center (NRRC) and the use of locally produced RUTF provided by the NRRC. An important aspect of this study was the simplified yet effective monitoring program CommCare which allowed health care workers to record data using mobile devices without the need of internet in places where it is limited or nonexistent and using paper-based surveys at the end of an intervention which was recorded into CommCare. This allowed easy access and sharing of information throughout the various administrative levels of the intervention. The data from CommCare was easy to input into Excel sheets to evaluate throughout and after the SNEHA project. Mixed-methods evaluations were conducted using a qualitative study interviewing 24 mothers and 13 staff members to assess intervention downfalls, and quantitative data analysis measuring the effectiveness of the project, overall. Quantitative analysis revealed;

“Households in comparison areas had a significantly higher likelihood of poverty than intervention areas (73.7% versus 71.4%). However, households in intervention areas reported a significantly higher level of food insecurity in terms of worrying whether the household would have enough food to eat (21.7% as compared with 18.1%).”

Most CMAM interventions need Non-profit and external support initially, especially for staff training and program structure. However, it becomes necessary to hand off the program to the government to ensure sustainability and to scale up. Case studies in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Malawi, and Niger suggest handing over programs to the government is feasible and the most effective option to maintain sustainability. Additionally, many children who have experienced SAM faced hurdles with low nutrition or moderate nutrition in the future along with various medical ailments that could be prevented through sustained government ran CMAMs and local hospitals.

A major reason for the success of the SNEHA-CMAM program is accredited to the community-led intervention method. Community-led interventions proved successful due to various reasons: there was a constant presence of field staff allowing administrative or logistical issues to be resolved quickly; a strong information sharing structure was implemented with field staff providing regular and updated information to the community members (usually mothers) in regards to SAM updates regarding their children; the field staff was persuasive by using a referral system to target families reluctant to accepting services (in cases of domestic abuse, or lack of child care, assistance from other nonprofits was utilized to treat afflicted children); and lastly, the case management provided by SNEHA was holistic assisting families in cases of vision correction, cleft palate surgery, vaccination, and the like along with SAM; the training and supervision provided to staff members was crucial to success because it held staff members accountable and armed them with tools and education to effectively manage cases. Mothers interviewed post-intervention felt that staff members were supportive and caring regularly checking in with the mothers; they believed the knowledge provided by health workers was useful and adopted the various recipes, cooking methods, hygiene, immunization, breastfeeding, and growth monitoring information recommended by health workers. The mothers reported feeling monitored as they often became enmeshed working or with household duties so the presence of frontline health workers within the community served as the optimal accountability strategy to aid and ensure mothers complied with necessary interventions.

Article 4

A study conducted in Uttar Pradesh in three districts (Barabanki, Sitapur, Hardoi) aimed at evaluating the Nutritional Rehabilitation Center (NRC), Accredited Social Health Activists ASHA, and Anganwadi workers present at the village level, via surveys of major stakeholders both staff and community members affected, this evaluation attempts to understand improvements necessary for future interventions. A major finding of this qualitative study was that mothers often lacked autonomy in buying nutritious food for children and even in reproductive rights; often leading to weak mothers overburdened by repeated pregnancies giving birth to malnourished children. Male household members usually purchased cheap, fatty, wheat-based, solid junk food which is given to children as early as age one. A major necessity recognized by this study was the need for caretakers (both mothers and fathers) to understand SAM is a disease with severe consequences which most did not consider. Caretakers only identified a child with SAM when they were facing severe physical symptoms due to SAM such as diarrhea, convulsions, cyanosis, vomiting, or the like. Most mothers were so familiar with undernourished children they reported their children as slightly small but overall healthy. Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat are similar culturally, still, understanding the specific locale context is crucial to every health intervention.

Article 5

One of the areas most affected by SAM in children is the Surat district of Gujarat. In Surat, there is a three-tier approach to child malnutrition being implemented. The first tier is Mission Balam Sukham which provides community-based management of malnutrition (long-term intervention) alongside an inpatient model (short-term intervention).

The Community Malnutrition Treatment Center (CMTC) in Mahuva, Surat is one of the physical locations where SAM interventions are being carried out. The Center can take in ten children at a time for inpatient treatments lasting 21 days within the facility. Through an assessment of one out of three CMTCs in Surat, Gujarat chosen randomly, certain strengths and weaknesses of existing interventions are revealed.

CMTCs in Surat have well established infrastructure, definite guidelines, clear policies, trained and motivated staff, support from higher-ups or supervisors (Block Health Officer and medical superintendent), timely fund allocations, support from other health functionaries, and an overall high success rate and satisfaction (determined when beneficiaries of the center were surveyed).

Still, the CMTCs fall short in funding receiving only ₹21,000, ₹18,000 of which is used for the cost of food preparation alone, which includes nutritional medication and vitamins added to the food. There is a broader Community Health Center (CHC) (which can include hospitals or clinics already in place) attached to the CMTCs. However, the CMTC often does not have pediatricians available on site, most of the work is being carried out by the medical officer and staff nurse permanently available at the center. Lastly, there is no district-level Nutritional Rehabilitation Center present at a civil hospital (as promised by the government) which hinders the three-tier approach of CMTC because children that undergo the CMTC intervention and still require additional services to combat emergencies are often unable to access civil hospitals without a referral from CMTC or the CHC.

Past Interventions in Gujarat, India

The Indian Government has developed a framework for addressing child malnutrition which is a part of the National Health Mission to reduce anemia in women aged 15-49, decrease out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures for Indian households, and to lower the infant mortality rates with a focus on nutrition. This is proposed via the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) which has a specific target, “to reduce under-nutrition among children aged 0–3 years to half of the NFHS-3 levels (NFHS-3 estimates undernutrition below 3 years at 40%, hence the 12th FYP is to reduce it to 20% by 2017).”

In the state of Gujarat, there is a direct link between mothers who are underweight and children prone to SAM. Nutritional statuses are worse among mothers who give birth in their teens. There is a lack of nutritional diversity with only 12% of children receiving the necessary dietary requirements while junk foods and foods low in nutrition are most often given to children ages 6-35 months. In Gujarat, 39% of the children are not receiving services from ICDS, only 40% of children ages 36-59 months are going to clinics to address SAM, while only 40% of children currently receive take-home rations. For children ages 6-8 months, around half of them are not receiving the necessary nutrients essential for early growth and development alongside breast milk. Stunting is most prevalent in Gujarat and the rates of stunting have actually gone up which points to a specific need for nutritional supplements. Vaccinations for polio, measles, and other illnesses necessary during childhood are not being covered so children susceptible to these illnesses due to weaker immune systems face additional challenges

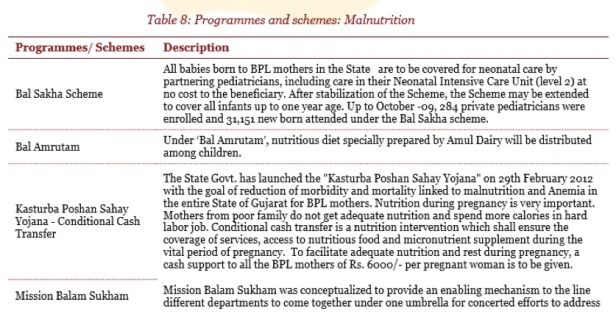

A graph released by the Government of Gujarat in 2014, points out the main administrative divisions where cases of SAM and malnourishment, in general, are most rampant. The Gujarat State Nutrition Mission has aligned with the Department of Women and Child Development, Health, Education, Rural Development, Tribal Development, Urban Development, Water Supply Development, and various other departments to implement preventive and curative aspects of malnutrition. Prevention strategies include the use of BCC to establish comprehensive nutrition programs, and utilizing community support networks such as the Panchayati Raj Institutions (local community leaders in rural areas of Gujarat), Self Help Groups, Sakhi Mandals (female support organizations), Doodh Mandlis (female support networks for motherhood related nutritional information) and certain other community groups able to mobilize and focus on local vulnerable populations. Additionally, the state of Gujarat has efforts in place to spread awareness of Infant and Young Child feeding practice by aligning these educational efforts with the existing Village Health, Sanitation, and Nutritional Committees. Curative or treatment aspects of the Gujarat State Nutrition Mission has created multiple Intensive Nutrition Care Centers, Child Malnutrition Treatment Centers, and Nutrition Rehabilitation Centers in new locations (creating new infrastructure) and within existing hospitals.

Even with these institutional interventions in place by the government of Gujarat, major gaps exist hindering the success of interventions. There is a lack of effective communication between the various healthcare services and regional versus district level teams for planning health interventions. Household food insecurity is difficult to address because access to nutritious foods for the most vulnerable populations (women age 15-44 and children up to 59 months of age) is hindered due to deficient storage facilities for food in certain regions. This issue makes access physically impossible even with cash transfers or rations, severely crippling long-term interventions. Protein Energy malnutrition is rampant as a cause of undernutrition due to poor feeding practices. There is a lack of available beds and resources within hospitals to adequately address child malnutrition. There is an overall lack in human resources in paramedical staff and public health care workers in Gujarat, which is especially concerning for rural areas. Due to a lack of resources and funding, there are inadequate training programs for skill building to address SAM in children. Lastly, there are no strict measures in place for quality control and information reporting systems as the collection, management, and generation of data is not institutionalized. This further affects the ability to train available staff and monitor and evaluate SAM interventions. The problem with Gujarat can be best summarized by noting the institutions necessary for eradicating SAM under children five years of age and under are there, but health interventions are inefficient or outright lacking, often due to funding concerns.

Recommended Health Intervention for <5 SAM in Gujarat, India;

Gujarat only has 14 CMTCs and the ICDS in Gujarat work only to subsidize nutritious food via food storage and redistribution which is imperative. Gujarat has a map of the various Anganwadi community worker training centers and trains supervisors for nutrition-related programs.

With 33 districts in Gujarat, having at least one CMTC or CMAM in each district is feasible. According to WHO 2005 data, the state has 53 district and taluk hospitals, 4 mental hospitals, 2 specialized hospitals and 60 dispensaries having a total bed capacity of 6648. Thus, Gujarat has enough hospitals to utilize for outpatient care.

The ICDS has used the Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) approach for treating SAM with four major components; outpatient RUTF distribution, a short-term inpatient clinic for stabilization, community mobilization, and a supplementary feeding program when appropriate in Dharavi Mumbai. Additionally, CMTCs in Surat Gujarat have also been successful. Therefore, the CMTC and CMAM approaches must be combined the create the optimal health intervention necessary in Gujarat to eradicate under 5 SAM in the next five years. Implementation of CMAM and CMTC must include;

Monitoring and Evaluation:

The Ministry of Health in India and the government of Gujarat already conducts surveys related to child malnutrition (specifically the Comprehensive Nutrition Survey in Gujarat). Since these data gathering institutions are in place, collecting monitoring and evaluation surveys based on the suggestions by the World Bank or even adopting PROMIS for CMTC centers throughout Gujarat is an achievable objective. While the evaluation methods must be context specific, CMTC has annual evaluations it already conducts and it surveys the beneficiaries who undergo inpatient treatment for SAM. These are forms of quantitative and qualitative assessments that are feasible for CMTCs across Gujarat to conduct and compile into a larger database to assess strengths and weakness before, throughout, and after the intervention process.

The prevalence of stunting in Gujarat makes it the most effective indicator to assess if interventions are successful in achieving the overall objective of full eradication of SAM. When the percentage of stunting in Gujarat continuously decreases, interventions can be denoted as successful according to the community context. While simply measuring stunting levels would be a disservice to implementing sustainable eradication of SAM for Gujarat, it serves as the most effective and feasible indicator for success in this region. This indicator is selected in accordance to WHO recommendations of measurable success rates of SAM interventions. The World Bank report on developing nations treatment indicators of SAM intervention is also a crucial resource that the Ministry of Health could utilize to evaluate the effectiveness of current CMTC centers.

Data Gathering and Analysis:

Since data gathering at extremely specific local levels is possible, the government would need to create a position for evaluation and compilation of the data into a larger database. This seems politically difficult. However, due to proven benefits of having data analysts by the WHO, World Bank, and previous projects in various nations already, there is enormous potential to advocate for such positions. The Ministry of Health has already declared specific pledges when it comes to child mortality and eradicating extreme hunger which gives advocacy potential to local citizens and civil society to demand certain institutional changes be created for better understanding the cost-benefit analysis of projects that are being funded by the government.

Additionally, Gujarat health care workers can adopt CommCare to bridge the gaps identified in communication between supervisors, AWWs, frontline health workers, municipal hospitals, and local CMTCs. Once the local communication hurdle has been overcome, a federal employee would just have to compile the CommCare data into Excel sheets and used accessible programs like STATA (which was utilized by the SNEHA intervention in Mumbai).

Funding:

Funding is a major issue for interventions for SAM in children under five. India spent only 3.89% of its GDP on health in 2015. Gujarat in 2011, spent only 0.57% of its budget on healthcare. The Gujarat Corporate Social Responsibility Authority identifies potential funding avenues via multinational and regional businesses that can be lobbied for funding. Additionally, CMTC center evaluations of Surat reveal potential funding accessible via Rogi Kalyan Samiti (which provides medications), private donations, and the ability to lobby the government to allocate more towards the healthcare budget.

There are many non-profits who have worked in urban slums in India in the past (UNICEF, World Vision, World Bank, WHO, and many local NGOs who partner with and lobby state governments for better SAM related interventions.

CMAM is a cost-effective program costing $23 per child on average according to various national studies. Gujarat, with a GDP of $2,200 per capita, can easily afford this intervention. Gujarat requires additional Nutritional rehabilitation centers (NRC) to provide locally sources RUTF. Gujarat has a large-scale agricultural community, thus local RUTF production is possible and cost-efficient.

Communication:

Multiple institutions are already in place throughout Gujarat so communication between them is possible. CMTCs currently staffs one nurse, one medical officer, one nutritionist, two cooks, and one cleaner. The nurse and medical officer are attached to the wider community health centers that the CMTC is under and the nutritionist can be hired from the local community to provide community-specific food. The nurse or medical officer at each CMTC can be assigned to communicate the impacts of interventions on their local community health center each week by providing an extra monetary incentive to carry out this role efficiently. Communication is possible in the most efficient manner according to the needs of a specific community whether that is via phone call, technology, or even physical mail in the format of a government issued form with specific questions that the nurse would simply have to answer to help the community health center understand what the CMTC may need, where it is weak in interventions, and the like. As noted in previous studies by the World Bank, WHO, and even specific country interventions, the pitfalls in communication that can make interventions unsuccessful are formed into suggestions in the World Bank report and various articles which address institutional communication. Developing a form based upon those communication needs for the CMTC to give to the community health center which would supply that information to the district level hospitals is a suggestion for effective interventions for child malnutrition in Gujarat. Communication is possible if all these resources for communication were combined with CommCare as a feedback mechanism.

Additionally, the most efficient form of communication has been to have a local supervisor within district contexts who overlooks frontline healthcare workers. The only role this position entails is monitoring frontline workers, receiving feedback from them, and passing off information to municipal hospitals or higher-ups in the administrative chain.

A combination of innovative communication methods and an additional position created for communication at the administrative level could dramatically impact the shortcomings Gujarat faces in communication.

Basic Nutritional Food Intervention/ Inpatient:

All CMTCs have in-house nutritionists responsible for providing foods with necessary nutrients. This is one of the most crucial roles of the CMTC staff members with one downfall, disappointing training. Training by the wider community health center must be provided to these nutritionists to ensure suggested guidelines outlined by the WHO report are being adopted into food preparation. Training methods and information building structures are already present within CMTCs for healthcare workers and volunteers. These pieces of training must be institutionalized to be conducted for any new staff members.

The best way to ensure sustainable training is by non-profit and local government partnerships as exemplified in multiple studies listed previously. The SNEHA and Anganwadi in Mumbai have the most effective community training guidelines created. Their organizational structure must be adopted in Gujarat, the organizational structure may be monitored based on the SNEHA study and adjusted for the context of Gujarat. Utilizing a non-profit initiative to develop and implement a year of effective training and then handing off the developed model of the government ran CMTC/CMAM has the most potential for success. The Gujarat government can partner with international NGOs (World Vision) or partner with SNEHA and Anganwadi organizations from Dharavi with experience in conducting efficient training about nutritious foods based on WHO suggestions and research.

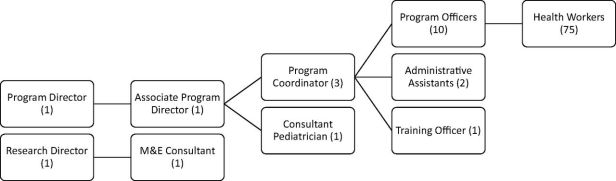

SNEHA CMAM Leadership

Multilateral Interventions:

Vaccinations are important Gujarat as children are prone to anemia, stunting, and ailments like polio or measles. CMTCs must evaluate children for odemea, water loss, diarrheal issues, and undernutrition using WHO guidelines for easy and accessible measurements for these conditions. Additionally, children with SAM attending CMTCs must be given necessary time sensitive vaccinations during hospital visits. Promotion of vaccination is possible via BCC training as well.

The Department of Health had been shown in the past to implement vaccination campaigns when necessary. Using their resources and local CMTC/CMAM evaluations of patients, each child that undergoes in-patient care at any CMTC/CMAM center in Gujarat could automatically be vaccinated if they have not been.

Preventive Care & BCC (Behavioral Care Communication):

Panchayat is a common administrative organization available in rural villages across India with access to limited budgets distributed by statewide governments. Local community members highly influence these political bodies and Panchayats are prone to listen to advocacy from the citizenry, especially when it comes to children and growth, as determined by the cultural context of Gujarat. Panchayats can spread nutritional training and provide nutritious food to local populations, which often addresses issues of access. Panchayats are community-based local actors who can work with SAM intervention staff to create effective BCC training modules to widely distribute to the population within rural communities.

The State of Gujarat has an Urban Development sector which has political bodies and community health workers present locally in urban settings which can be accessed to create BCC training modules in the specific context of the urban area. The guidelines for what basic BCC training programs should cover are provided in the WHO report and can be simply duplicated as a foundation to build context-specific BCC training regiments for both the urban and rural settings in various areas of Gujarat. For example, training must be provided to males in households who purchase food for the family opt ensure nutritious food is prioritized over the cheapest food. NRCs within Gujarat provide nutritious food but can lack in impact and ability to reach all those who need it. Therefore, partnering with local means of agriculture (usually Panchayats have this information) to determine the most nutritious food found in a certain district is the best way for CMTCs/CMAMs to implement preventive care across urban and rural settings.

Focus on women especially is necessary to ensure sustainable interventions to address SAM. This is achievable by utilizing the Women and Children’s Health Ministry, Sakhi Mandals, and Doodh Mandlis to empower women financially and educate them on nutrition in a safe, comfortable, and community-driven setting.

Human Resources/ Motivation:

As identified in the CSR Report, there are many local civil society organizations present across Gujarat which often have access to community health workers and volunteers. Therefore, volunteer recruitment from these organizations in every local area must be carried out. In terms of healthcare workers specifically, Gujarat must offer more financial incentives for nurses and healthcare professionals throughout the state. This is possible via funding projects to encourage health workers and assessing their specific issues leading to a lack of motivation via surveys.

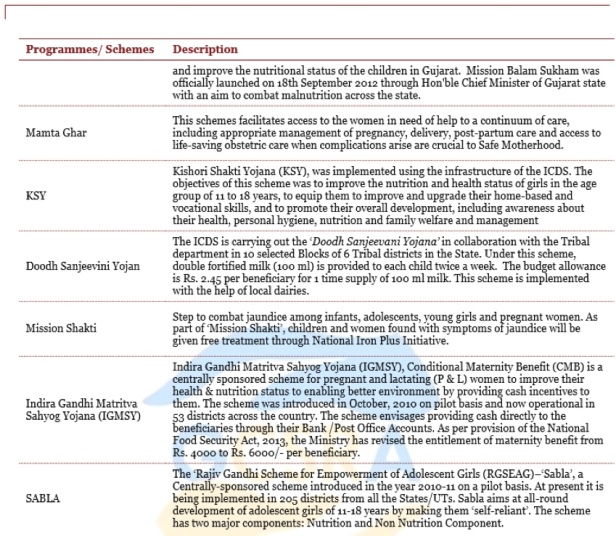

![]() Gujarat CSR Authority. (2015). Malnutrition Information Pack.Retrieved from GCSRA: http://gcsra.org/writereaddata/images/pdf/IP-Malnutrition.pdf, p 13.

Gujarat CSR Authority. (2015). Malnutrition Information Pack.Retrieved from GCSRA: http://gcsra.org/writereaddata/images/pdf/IP-Malnutrition.pdf, p 13.

Scaling Up:

A repeated issue throughout previous assessments reveals children affected by SAM come from similar backgrounds and often end up migrating in the middle of an intervention. Thus, large-scale implementation of interventions and data sharing among the various ICDS, CMAMs, and nonprofits working with children affected by SAM is crucial. Additionally, if this intervention were to be implemented nationally, the issue of leaving an intervention halfway due to migration would be resolved via a governmental requirement of at least one CMAM/CMTC per district throughout the nation.

For a nation-wide SAM implementation, communication would have to be conducted more effectively using multiple platforms not just CommCare both in the field and administratively. RUTF interventions must include local food context. Urban and rural areas must be differentiated between. Monitoring and evaluation must be taken up by the federal government. The government must utilize international and local non-profit help to get a federal program started initially. Overall, scaling-up of CMTC/CMAM programs would require assessing the infrastructure with the potential for addressing SAM currently present, as was done with Gujarat, and using an evaluation to reform existing infrastructure to address the goal of eradicating under-five child malnutrition more efficiently.

Conclusion

Gujarat can utilize the institutions it already has in place more effectively with a focus on; monitoring and evaluation, data gathering and analysis, more funding, institutionalized communication methods, adopting multilateral health interventions, focusing on preventive care, understanding nutritional needs, providing targeted nutritional training, and focusing on human resources via reward systems. While these interventions are challenging, focusing on WHO guidelines, World Bank reports and learning from past interventions, to reform CMTC/CMAM programs is the most cost-effective strategy Gujarat can adopt. Additional assessments can be created to scale up the existing interventions already in place in districts throughout India.

(PS: HERE IS A PDF VERSION W/ FOOTNOTES)

Works Consulted

Agee, M. (2010). Reducing child malnutrition in Nigeria: Combined effects of income growth and provision of information about mothers’ access to health care services. Social Science & Medicine,71(11), 1973-1980.

Blössner, Monika, de Onis, Mercedes. Malnutrition: quantifying the health impact at national and local levels. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005. (WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series, No. 12).

Bora JK, Saikia N (2018) Neonatal and under-five mortality rate in Indian districts with reference to Sustainable Development Goal 3: An analysis of the National Family Health Survey of India (NFHS), 2015–2016. PLoS ONE 13(7): e0201125. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0201125

Community-Based Management of Acute Malnutrition to Reduce Wasting in Urban Informal Settlements of Mumbai, India: A Mixed-Methods EvaluationNeena Shah More, Anagha Waingankar, Sudha Ramani, Sheila Chanani, Vanessa D’Souza, ShantiPantvaidya, Armida Fernandez, Anuja JayaramanGlobal Health: Science and Practice Mar 2018, 6 (1) 103-127; DOI: 10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00182

Thank you for post this blog and it seems good information, which can helps more and to get better solution.

LikeLike

Great blog. People think just exercising can control your weight. They have to understand nutrition and what we eat is 80% of our weight loss journey.

Regards,

Nutrition health services in birmingham

LikeLike

Thanks for reading. This analysis is focused on children who are malnourished and not losing weight but I understand what you mean that your body’s responses to food are crucial when it comes to health and a food intake is an ideal method to make sure you feel healthiest.

LikeLike